“Carlos” (2010) and other films I’ve seen this month

Olivier Assayas’ Carlos is an engrossing, five and a half hour recount of the career of notorious terrorist Carlos the Jackal. It was released as a TV mini-series and is only recently being re-released in theaters. The picture shares the flavor of the Bourne movies, the international events, seemingly endless, world-wide shooting locations and bursts of violence. But of course Carlos is a real man, not a super hero. Likewise, Assayas avoids the jarring, hand held camera and rapid fire editing of the Bourne series.

Olivier Assayas’ Carlos is an engrossing, five and a half hour recount of the career of notorious terrorist Carlos the Jackal. It was released as a TV mini-series and is only recently being re-released in theaters. The picture shares the flavor of the Bourne movies, the international events, seemingly endless, world-wide shooting locations and bursts of violence. But of course Carlos is a real man, not a super hero. Likewise, Assayas avoids the jarring, hand held camera and rapid fire editing of the Bourne series.

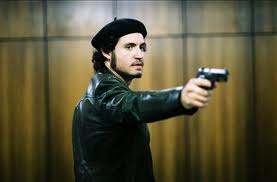

The movie’s strength stems from Edgar Ramirez, the actor playing Carlos. He fluidly moves from passive arrogance to aggressive violence, speaks several languages and transforms his body from a lean youth to a doughy, aging man. As Assayas tells it to us, Carlos is a man of intense ego and insatiable ambition, with addictions to women and alcohol. Yet he is also incredibly intelligent and driven by vengeful anger that can only come from long experience with injustice. Ramirez internalizes all of these elements, brooding on them and allowing them to surface only sometimes, and not always when we expect.

Carlos seems to be more anti-capitalist than pro-communist. He seeks to tear down, rather than build. He envisions himself as a weapon to be used by governments who share his goals, though as his fame grows, he begins to think in reverse. In the 1970’s and 80’s, he allies himself with the likes of Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi. But by the early 90’s he has lost the support of nearly every Middle Eastern and North African country, who see him as a wild card and a liability. As one of Carlos’ friends remarks near the end, “We have lost”. The capitalists had “won”, turning Carlos into a soldier with no war to fight.

Quite a lot of the film is in heavily accented, often mumbled English, obscuring a line here and there. But most of it is smooth, and of course there are subtitles for the half dozen or so other languages that are spoken. At the very end of the film, we see pictures of the real people involved, and the casting (by Antoinette Boulat) is, at least in terms of looks, strikingly good.

I also saw two films by Pier Paulo Pasolini this month:

I also saw two films by Pier Paulo Pasolini this month:

Hawks and Sparrows (1964)

I cannot quite say that this is a good movie. Yet Pasolini’s creativity and originality overwhelm the disjointed storytelling and the occasional dip into the ridiculous.

Hawks and Sparrows is a not-so-subtle satire of1960′s Italian politics, Christianity and Marxism. The message feels like it comes from an agnostic, saying, “Well, I don’t know the answers, but aren’t we funny for seeking them?” All of that is mildly interesting, but the real fun of the movie is the old man, his son and the left-wing intellectual talking crow that won’t leave them alone.

The Decameron (1971)

Pasolini approached this film in nearly the opposite manner to Hawks; the production value is much higher, the story is amusing and relatively fluid, and there is very little pretense of “message” or “meaning”. Simple stories convey broad ideas, with little need to dig for them.

The Medieval morality tales are changed a bit from Boccacio’s versions, and of course only a handful are represented. The lurid sexual events only hinted at in the written form are brazenly displayed in the film, lending a kick of energy and realism to the otherwise tall-tale style. It earns quite a few laughs, and the pace matches the fun, making for an easy, entertaining ride. The cinematography is particularly good.

Secret of Kells (2009), dir. by Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey

Secret of Kells (2009), dir. by Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey

This fun animated adventure uses a style that reminds me of the Samurai Jack tv series. It is jagged, simple and very expressive. An Irish abbey is besieged by Vikings, and Brendan, a 12 year-old boy, is tasked with saving and completing a magical book.

There is an epic feel (though the movie is only 75 minutes long), as Vikings are transformed into monstrous giants, the woods are filled with fairies, wolves and demons, and stunning pictures are drawn with bright, magical inks. A young man must come of age to become a hero, yet his world is even less predictable than Frodo’s in the Lord of the Rings.